List of Johnson solids

In geometry, polyhedra are three-dimensional objects where points are connected by lines to form polygons. The points, lines, and polygons of a polyhedron are referred to as its vertices, edges, and faces respectively.[1] A polyhedron is considered to be convex if:[2]

- The shortest path between any two of its vertices lies either within its interior or on its boundary

- None of its faces are coplanar—they do not share the same plane, and do not "lie flat"

- None of its edges are colinear—they are not segments of the same line.

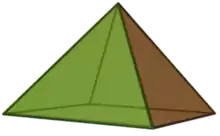

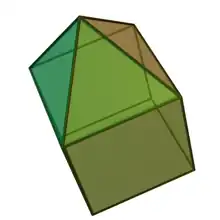

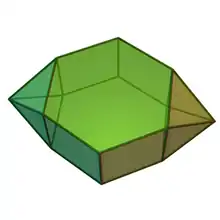

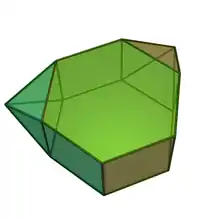

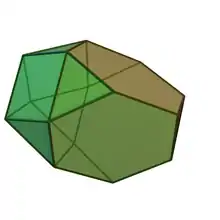

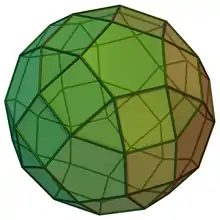

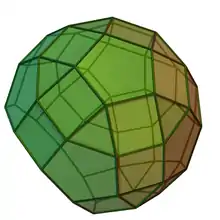

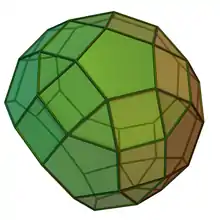

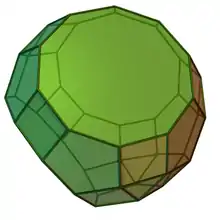

A polyhedron is said to be regular if its faces are equilateral and equiangular.[3] Regular polyhedra with the additional property of vertex-transitivity are called uniform polyhedra.[4] A Johnson solid (or Johnson–Zalgaller solid) is any convex polyhedron with only regular polygons as its faces.[5] Some authors exclude uniform polyhedra—which include the Platonic solids and Archimedean solids, as well as prisms and antiprisms—from their definition.[6]

The Johnson solids are named for the mathematician Norman Johnson (1930–2017), who published a list of 92 convex polyhedra conforming with the above definition in 1966. Moreover, Johnson conjectured that the list was complete, and there could not be any other examples. Johnson's conjecture was later proven by the Russian-Israeli mathematician Victor Zalgaller (1920–2020) in 1969.[7] The first six Johnson solids are the square pyramid, pentagonal pyramid, triangular cupola, square cupola, pentagonal cupola, and pentagonal rotunda. These solids may be applied to construct another polyhedron that has the same properties, a process known as augmentation; attaching prism or antiprism to those is known as elongation or gyroelongation respectively. Some others may be constructed by diminishment, the removal of those from the component of polyhedra, or by snubification, a construction by cutting loose the edges, lifting the faces and rotate in certain angle, after which adding the equilateral triangles between them.[8]

The following table contains the 92 Johnson solids of the edge length . Here, the table includes the enumeration of Johnson solid (denoted as )[9]. It also includes the number of vertices, edges, and faces, symmetry, surface area , and volume . As for the background, every polyhedron has its own characteristics, including symmetry and measurement. An object is said to be symmetrical if there is such transformation preserving the immunity to change. All of those transformations may be composed in a concept of group, alongside the number of elements, known as order. In two-dimensional space, these transformations include rotating around the center of a polygon and reflecting an object around the perpendicular bisector of a polygon. A polygon that is rotated symmetrically in is denoted by , a cyclic group of order ; combining with the reflection symmetry results in the symmetry of dihedral group of order .[10] In three-dimensional symmetry point groups, the transformation of polyhedra's symmetry includes the rotation around the line passing through the base center, known as axis of symmetry, and reflection relative to perpendicular planes passing through the bisector of a base; this is known as the pyramidal symmetry of order . Relatedly, polyhedra that preserve their symmetry by reflecting it across a horizontal plane are known as prismatic symmetry of order . The antiprismatic symmetry of order preserves the symmetry by rotating its half bottom and reflection across the horizontal plane.[11] The symmetry group of order preserves the symmetry by rotation around the axis of symmetry and reflection on horizontal plane; one case that preserves the symmetry by one full rotation and one reflection horizontal plane is of order 2, or simply denoted as .[12] The mensuration of polyhedra includes the surface area and volume. An area is a two-dimensional measurement calculated by the product of length and width, and the surface area is the overall area of all faces of polyhedra that is measured by summing all of them.[13] A volume is a measurement of the region in three-dimensional space.[14] The volume of a polyhedron may be determined by involving its base and height (as in pyramids and prisms), slicing it off into pieces after which summing them up, or finding the root of a polynomial representing the polyhedron.[15]

Notes

- Meyer (2006), p. 418.

- Cromwell (1997), p. 77.

- Diudea (2018), p. 40.

- Diudea (2018), p. 39.

- Uehara (2020), p. 62.

-

- Powell (2010), p. 27

- Solomon (2003), p. 40

- Flusser, Suk & Zitofa (2017), p. 126.

- Walsh (2014), p. 284.

- Parker (1997), p. 264.

- Johnson (1966).

- Berman (1971).

References

- Berman, M. (1971). "Regular-faced convex polyhedra". Journal of the Franklin Institute. 291 (5): 329–352. doi:10.1016/0016-0032(71)90071-8. MR 0290245.

- Boissonnat, J. D.; Yvinec, M. (June 1989). Probing a scene of non convex polyhedra. Proceedings of the fifth annual symposium on Computational geometry. pp. 237–246. doi:10.1145/73833.73860.

- Cromwell, P. R. (1997). Polyhedra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521664059.

- Diudea, M. V. (2018). Multi-shell Polyhedral Clusters. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64123-2. ISBN 978-3-319-64123-2.

- Flusser, J.; Suk, T.; Zitofa, B. (2017). 2D and 3D Image Analysis by Moments. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hergert, W.; Geilhufe, M. (2018). Group Theory in Solid State Physics and Photonics: Problem Solving with Mathematica. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-41300-3.

- Holme, Au. (2010). Geometry: Our Cultural Heritage. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14441-7. ISBN 978-3-642-14441-7.

- Johnson, N. (1966). "Convex Solids with Regular Faces". Canadian Journal of Mathematics. 18: 169–200. doi:10.4153/CJM-1966-021-8.

- Litchenberg, D. R. (1988). "Pyramids, Prisms, Antiprisms, and Deltahedra". The Mathematics Teacher. 81 (4): 261–265. JSTOR 27965792.

- Meyer, W. (2006). Geometry and Its Applications. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-369427-0.

- Parker, S. P. (1997). Dictionary of Mathematics. McGraw-Hill.

- Powell, R. C. (2010). Symmetry, Group Theory, and the Physical Properties of Crystals. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7598-0. ISBN 978-1-4419-7598-0.

- Rajwade, A. R. (2001). Convex Polyhedra with Regularity Conditions and Hilbert's Third Problem. Texts and Readings in Mathematics. Hindustan Book Agency. doi:10.1007/978-93-86279-06-4. ISBN 978-93-86279-06-4.

- Solomon, R. (2003). Abstract Algebra. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-4795-4.

- Slobodan, M.; Obradović, M.; Ðukanović, G. (2015). "Composite Concave Cupolae as Geometric and Architectural Forms" (PDF). Journal for Geometry and Graphics. 19 (1): 79–91.

- Timofeenko, A. V. (2009). "The Non-Platonic and Non-Archimedean Noncomposite Polyhedra". Journal of Mathematical Sciences. 162 (5): 710–729. doi:10.1007/s10958-009-9655-0.

- Todesco, G. M. (2020). "Hyperbolic Honeycomb". In Emmer, M.; Abate, M. (eds.). Imagine Math 7: Between Culture and Mathematics. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42653-8. ISBN 978-3-030-42653-8.

- Uehara, R. (2020). Introduction to Computational Origami: The World of New Computational Geometry. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-4470-5. ISBN 978-981-15-4470-5.

- Walsh, E. T. (2014). A First Course in Geometry. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-78020-7.

- Williams, K.; Monteleone, C. (2021). Daniele Barbaro’s Perspective of 1568. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-76687-0. ISBN 978-3-030-76687-0.

- Zalgaller, V. A. (1969). Convex Polyhedra with Regular Faces. Consultants Bureau. ISBN 978-1-4899-5671-2.

External links

- Gagnon, Sylvain (1982). "Convex polyhedra with regular faces" (PDF). Topologie Structurale [Structural Topology] (in French) (6): 83–95.

- Hart, George W. "Johnson Solid".

- "Johnson Polyhedra: Polyhedra with Regular Polygon Faces". See all of the categorized 92 Johnson solids images on one page.

- "Johnson Solids".

- Vladimir, Bulatov. "VRML models of Johnson Solids".